As we near the publication of the 2013 craft brewer data set, I’ve been thinking a lot about the states. In the medium/long run, the most important stories about craft brewing are state stories. How high is the peak in Oregon, Colorado, and Vermont? Can the Southeast catch up with the rest of the country? What new states (Texas, North Carolina, Florida) will emerge as regional powerhouses? While the majority of these state stories will derive from the relationship between local brewers and beer lovers, the individual regulatory environments of the states will be a powerful force in structuring those relationships.

One of the categories of regulation that may matter most is self-distribution. Before going further, let me reiterate the BA’s position in support of a truly independent three-tier beer distribution system. Independent distributors provide efficiency and access to markets. That said, not all brewers or brands have adequate sales levels to find distribution. In those cases, self-distribution for small brewers is a common-sense solution. It allows small brewers access to consumers as they build brands, and allows wholesalers to see the success of brands/brewers before they bring them into distribution. This ability to start through self-distribution allows more entrants market access, which is fundamental to a free, competitive marketplace.

The effect of self-distribution laws on outcomes is striking (stats 101 note: correlation is not causation; in addition to the possibility of reverse causation [that brewer success causes changes in laws], it’s highly likely that self-distribution laws are only one part of a more complex regulatory environment causing these results [i.e. states with self-distribution laws probably have other rules favorable to craft brewers]). First, let’s look at craft breweries per capita. 15 states (including D.C.) do not allow self-distribution, whereas 33 do (3 have a limited form and are not included in this analysis). In the graph below, each dot is a state. The contrast is stark. States with self-distribution have 1.41 craft breweries per 100,000 21+ adults. States without self-distribution have 0.77 (for categories, I’m using population-weighted averages; non-weighted state averages have an even bigger gap; 2.1 for self-distribution states and 1.0 for non-self-distribution states).

For those calculating at home, that gap is statistically significant with a p < 0.05 (two-tailed test). That means there is less than a 5% chance you’d get a difference that big randomly and strongly suggests that the independent variable in question (self-distribution) has a relationship with the dependent variable (number of craft breweries). So there’s a high probability that self-distribution laws (either by themselves or in tandem with other regulation) help more breweries get off the ground. Makes sense, right?

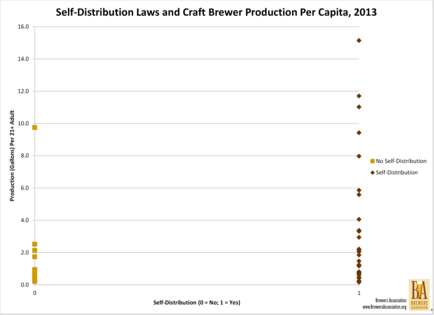

The same pattern emerges when we look at production. With the exception of one outlier state, the states with no ability to self-distribute are clustered at the bottom of per-capita production by craft breweries (average = 1.05 gallons produced per 21+ adult) whereas states with the ability to self-distribute average higher levels of production (average = 2.51 gallons produced per 21+ adult). Once again this difference is statistically significant with a p < 0.05 (two-tailed test).

It strikes me that the outcomes on the right of these two charts are what everyone should want:

- Brewers have increased market access.

- Beer lovers get more choice in the form of more breweries and more brands.

- Wholesalers gain confidence by investing in more established brands (not to mention they sell more high-value beer from craft brewers).

- States get more tax revenue and increased employment.

So what’s not to love about self-distribution for small brewers?

Resource Hub

Resource Hub