In the 2015 world of craft brewing, every week seems to bring news of a new acquisition or merger. Given this recent flurry of deals in the craft beer community, I’ve begun to hear a lot of musing about how consolidation of craft brewing is inevitable in the long run. While forecasting the future is notoriously difficult, I think there are as many structural factors pushing against consolidation as there are factors pushing toward it. So I thought it might be helpful to do a more rigorous analysis of the beer market, how consolidated it is, how it’s evolving, and what this means for the future.

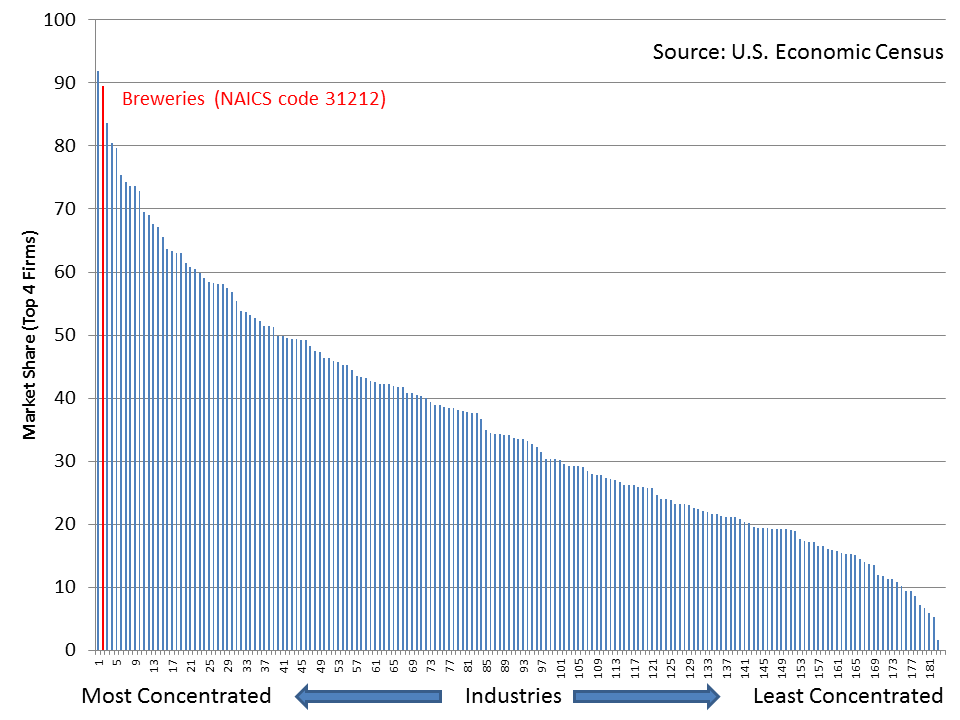

First, let’s start with the present. The large brewer end of the beer market is already ridiculously consolidated. According to the Economic Census, the top four manufacturers in the brewing industry (NAICS code 31212) control 89.5% of the market and the top eight control 91.5%. Everyone is so used to concentration that it’s easy to forget that a concentration level like that is actually an anomaly, whether you’re talking about beer across the world or manufacturing in the U.S.

For instance, the top eight firms currently control about 30% of the German beer market. Looking within the U.S., if you use the Economic Census, the average for manufacturing industries is 48% for the top eight firms, and the median is 46%. For the top four, the average is 36% and the median is only 34%. Here’s a graph showing the share the top four firms have in every American manufacturing industry, with breweries highlighted in red.

This extreme brewery consolidation has caused what is known in the social sciences as an opportunity structure: large firms became so consolidated and focused on the center of the marketplace that it was inevitable smaller firms (in this case small, independent breweries) would come along to succeed in niches they were forgetting (localized products, diverse styles, etc.). Most of the academic literature about the genesis of craft brewing focuses on these niches, either from a social movement perceptive or from a resource-partitioning viewpoint. In either case consolidation leads to commoditization and commoditization opens market spaces for businesses that differentiate. The point of acquisitions by the large brewers is to try to close those niches, but that may be more difficult than they imagine.

Now you might be saying to yourself, why can’t the big brewers just do what craft brewers have done, but at a larger scale and a lower cost structure? If you’ve ever taken an economics class, you’ve probably learned about the advantages of scale economics. Up to a certain point, getting bigger just makes things more efficient. More specifically, economists have a concept called “minimum efficient scale” (MES), the smallest production level at which average costs are minimized. Estimates of what this level is vary, but many show that the Brewers Association definition of small (6 million bbls) is around the point at which MES is reached (see Tremblay and Horton, 2005 for a summary of these studies).

While those theories may be useful to a certain point, beer isn’t the widget you learned about in Econ 101. Economies of scale only work like they do in an econ textbook when every product is the same, regardless of the size of production. Much of the value of craft brewers is derived from things that are very difficult to execute at scale, or when scaled even lose part their value. Things like:

- The service component of your local microbrewery taproom or brewpub

- Local branding or ingredients

- Limited batches and special releases tied to a particular event or cause

- The ability to rapidly pivot into new styles or products

- Close personal connections with communities and employees

That means scale is a dominant strategy only when we think of beer purely as a commodity, something the whole craft brewing movement shows isn’t true.

The Tradeoff

In the end, we can boil down the pushes and pulls of consolidation into two different (and somewhat opposing) factors. How does:

A. The value added of brewers remaining small, independent, and local line up against

B. The scale efficiencies from consolidation

The equilibrium between A and B will be decided by preferences of beer lovers. How much does independence matter to them (it is already clear it matters to many)? How much are they willing to tolerate consolidation? How much are they willing to pay for variety or locally-focused brands?

A sub question in this trade-off is how much integrating the service component with brewing matters. One trend that I’m continuing to watch is the increasing volume of beer being sold directly at breweries. Because of this, I think it’s important to separate the number of breweries from the more general market. The number of breweries is unlikely to go down anytime soon and is increasingly looking like industries that are hard to consolidate (restaurants, bars, etc.), with a variety of nimble players.

The Future

Back to the original question: what does this all mean for the future of the brewery consolidation? While anyone who claims to know definitively is probably trying to sell you something, I believe that the advantages of being small – both in terms of value added and in terms of nimble market action – will lead to an increasingly fragmented, rather than an increasingly consolidated industry. As evidence, I’ll point to two things:

1. The acquisitions by large brewers in recent years have been far outweighed by other shifts in the marketplace. If you add up Blue Point, 10 Barrel, and Elysian, ABI added about 150,000 bbls to its portfolio (plus any growth from Blue Point this year). Given recent market trends, that stems about 2 ½ weeks of share shift, and less if you include Mexican imports.

2. The fastest growing section of craft brewing is the smallest. To me, this suggests that small, nimble, and local is still an advantage (even within craft) and that there is a next generation of microbreweries ready to step up and become the local brewery for areas where consolidation happens.

None of this considers secondary factors like wholesaler consolidation, regulatory changes, anti-trust concerns, or retail structure. Although all of those matter, in the end, the beer lover is the final arbiter of the market, and the aggregated micro decisions about small and local versus scale will be the difference. Given the current trend in those decisions, I think fragmentation, rather than consolidation is going to be the order of the day for quite some time.

Resource Hub

Resource Hub